what argument did frederick jackson turner make to justify american imperialism?

The Borderland Thesis or Turner'south Thesis (also American frontierism) is the argument advanced by historian Frederick Jackson Turner in 1893 that a settler colonial exceptionalism, under the guise of American democracy, was formed past appropriation of the rugged American frontier. He stressed the process of "winning a wilderness" to extend the frontier line further for U.S. colonization, and the impact this had on pioneer civilization and character. In essence, Indigenous land possesses an "American ingenuity" that settlers are compelled to forcibly advisable to create cultural identity that differs from their European ancestors.[ane] Turner's text follows in a long line of thought within the framework of Manifest Destiny established decades earlier. He stressed in this thesis that American democracy was the primary result, along with egalitarianism, a lack of interest in bourgeoisie or high culture, and violence. "American democracy was built-in of no theorist's dream; information technology was not carried in the Susan Abiding to Virginia, nor in the Mayflower to Plymouth. Information technology came out of the American forest, and it gained new strength each fourth dimension it touched a new frontier," said Turner.[2]

In the thesis, the American frontier established liberty from European mindsets and eroding old, dysfunctional customs. Turner'due south platonic of frontier had no demand for standing armies, established churches, aristocrats or nobles; at that place was no landed gentry who controlled the land or charged heavy rents and fees. Frontier land was practically costless for the taking according to Turner. The Borderland Thesis was first published in a paper entitled "The Significance of the Frontier in American History", delivered to the American Historical Clan in 1893 in Chicago. He won broad acclaim amongst historians and intellectuals. Turner elaborated on the theme in his avant-garde history lectures and in a serial of essays published over the side by side 25 years, published along with his initial paper as The Frontier in American History. [three]

Turner's emphasis on the importance of the borderland in shaping American graphic symbol influenced the estimation found in thousands of scholarly histories. Past the fourth dimension Turner died in 1932, 60% of the leading history departments in the U.S. were instruction courses in frontier history along Turnerian lines.[4]

Summary [edit]

Turner begins the essay by calling to attention the fact that the western frontier line, which had defined the entirety of American history up to the 1880s, had concluded. He elaborates by stating,

Behind institutions, behind constitutional forms and modifications, prevarication the vital forces that call these organs into life and shape them to meet changing conditions. The peculiarity of American institutions is, the fact that they have been compelled to adapt themselves to the changes of an expanding people to the changes involved in crossing a continent, in winning a wilderness, and in developing at each area of this progress out of the primitive economic and political atmospheric condition of the frontier into the complexity of city life.

Co-ordinate to Turner, American progress has repeatedly undergone a cyclical process on the borderland line as society has needed to redevelop with its move w. Everything in American history upward to the 1880s somehow relates the western frontier, including slavery. In spite of this, Turner laments, the frontier has received footling serious study from historians and economists.

The borderland line, which separates civilization from wilderness, is "the most rapid and effective Americanization" on the continent; it takes the European from across the Atlantic and shapes him into something new. American emigration west is non spurred by authorities incentives, just rather some "expansive power" inherent within them that seeks to dominate nature. Furthermore, there is a need to escape the confines of the Country. The nearly important attribute of the borderland to Turner is its issue on republic. The frontier transformed Jeffersonian democracy into Jacksonian democracy. The individualism fostered by the frontier's wilderness created a national spirit complementary to commonwealth, as the wilderness defies command. Therefore, Andrew Jackson'due south make of popular commonwealth was a triumph of the borderland.

Turner sets up the East and the West as opposing forces; as the West strives for freedom, the Due east seeks to control information technology. He cites British attempts to stifle western emigration during the colonial era and as an example of eastern command. Even afterwards independence, the eastern declension of the U.s. sought to control the West. Religious institutions from the eastern seaboard, in particular, battled for possession of the West. The tensions between small churches as a result of this fight, Turner states, exist today considering of the religious attempt to main the Due west and those effects are worth further study.

American intellect owes its class to the frontier as well. The traits of the frontier are "coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness; that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that masterful grasp of textile things, lacking in the artistic but powerful to effect groovy ends; that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism, working for good and for evil, and however that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom."

Turner concludes the essay by saying that with the stop of the frontier, the first period of American history has ended.[five]

Intellectual context [edit]

Germanic germ theory [edit]

The Frontier Thesis came about at a time when the Germanic germ theory of history was pop. Proponents of the germ theory believed that political habits are adamant by innate racial attributes.[six] Americans inherited such traits as adaptability and cocky-reliance from the Germanic peoples of Europe. According to the theory, the Germanic race appeared and evolved in the aboriginal Teutonic forests, endowed with a great capacity for politics and authorities. Their germs were, directly and past mode of England, carried to the New World where they were immune to germinate in the Due north American forests. In so doing, the Anglo-Saxons and the Germanic people's descendants, beingness exposed to a forest similar their Teutonic ancestors, birthed the costless political institutions that formed the foundation of American regime.[vii]

Historian and ethnologist Hubert Howe Bancroft articulated the latest iteration of the Germanic germ theory just three years before Turner's paper in 1893. He argued that the "tide of intelligence" had always moved from east to west. Co-ordinate to Bancroft, the Germanic germs had spread across of all Western Europe by the Middle Ages and had reached their elevation. This Germanic intelligence was only halted by "ceremonious and ecclesiastical restraints" and a lack of "free country."[8] This was Bancroft's caption for the Dark Ages.

Turner's theory of early American development, which relied on the frontier as a transformative force, starkly opposed the Bancroftian racial determinism. Turner referred to the Germanic germ theory by name in his essay, claiming that "as well exclusive attention has been paid by institutional students to the Germanic origins."[9] Turner believed that historians should focus on the settlers' struggle with the frontier as the goad for the creation of American character, not racial or hereditary traits.

Though Turner'south view would win over the Germanic germ theory'due south version of Western history, the theory persisted for decades subsequently Turner's thesis enraptured the American Historical Association. In 1946, medieval historian Carl Stephenson published an extended article refuting the Germanic germ theory. Apparently, the conventionalities that costless political institutions of the U.s.a. spawned in ancient Germanic forests endured well into the 1940s.[x]

Racial warfare [edit]

A similarly race-based estimation of Western history also occupied the intellectual sphere in the United States before Turner. The racial warfare theory was an emerging belief in the late nineteenth century advocated by Theodore Roosevelt in The Winning of the West. Though Roosevelt would afterward have Turner'south historiography on the West, calling Turner's work a correction or supplementation of his own, the 2 certainly contradict.[11]

Roosevelt was not entirely unfounded in maxim that he and Turner agreed; both Turner and Roosevelt agreed that the frontier had shaped what would become distinctly American institutions and the mysterious entity they each called "national character." They also agreed that studying the history of the West was necessary to face the challenges to commonwealth in the tardily 1890s.[12]

Turner and Roosevelt diverged on the exact aspect of frontier life that shaped the contemporary American. Roosevelt contended that the germination of the American character occurred non with early settlers struggling to survive while learning a strange land, but "on the cutting edge of expansion" in the early battles with Native Americans in the New World. To Roosevelt, the journey west was one of nonstop encounters with the "hostile races and cultures" of the New World, forcing the early on colonists to defend themselves as they pressed forward. Each side, the Westerners and the native savages, struggled for mastery of the land through violence.[13]

Whereas Turner saw the development of American character occur just behind the frontier line, as the colonists tamed and tilled the land, Roosevelt saw information technology class in battles only across the borderland line. In the end, Turner's view would win out amid historians, which Roosevelt would take.

Evolution [edit]

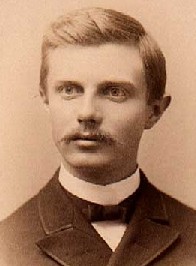

Frederick Jackson Turner, c. 1890

Turner set up an evolutionary model (he had studied evolution with a leading geologist, Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin), using the time dimension of American history, and the geographical infinite of the country that became the United States.[14] [15] The first settlers who arrived on the east coast in the 17th century acted and thought like Europeans. They adapted to the new physical, economic and political surroundings in certain ways—the cumulative effect of these adaptations was Americanization.

Successive generations moved further inland, shifting the lines of settlement and wilderness, but preserving the essential tension between the two. European characteristics cruel by the wayside and the old country'southward institutions (due east.1000., established churches, established aristocracies, standing armies, intrusive government, and highly diff land distribution) were increasingly out of place. Every generation moved further west and became more than American, more democratic, and more intolerant of bureaucracy. They also became more violent, more individualistic, more than distrustful of authority, less artistic, less scientific, and more dependent on advertizing-hoc organizations they formed themselves. In wide terms, the further west, the more than American the community.[xvi]

Closed frontier [edit]

Turner saw the land frontier was catastrophe, since the U.Southward. Demography of 1890 had officially stated that the American frontier had broken upward.[17] [eighteen] [xix] [20]

By 1890, settlement in the American West had reached sufficient population density that the frontier line had disappeared; in 1890 the Census Agency released a bulletin declaring the closing of the borderland, stating: "Up to and including 1880 the country had a frontier of settlement, but at present the unsettled surface area has been so broken into by isolated bodies of settlement that there tin hardly be said to be a frontier line. In the discussion of its extent, its westward movement, etc., information technology can not, therefore, whatsoever longer have a place in the demography reports."[21]

Comparative frontiers [edit]

Historians, geographers, and social scientists take studied frontier-like conditions in other countries, with an eye on the Turnerian model. South Africa, Canada, Russia, Brazil, Argentina and Australia—and fifty-fifty ancient Rome—had long frontiers that were also settled by pioneers.[22] However these other frontier societies operated in a very difficult political and economic environment that made commonwealth and individualism much less likely to appear and it was much more difficult to throw off a powerful royalty, standing armies, established churches and an aristocracy that endemic near of the land. The question is whether their frontiers were powerful enough to overcome conservative central forces based in the metropolis.[23] Each nation had quite unlike borderland experiences. For case, the Dutch Boers in South Africa were defeated in war by United kingdom. In Australia, "mateship" and working together was valued more than individualism.[24]

Impact and influence [edit]

Turner's thesis quickly became popular among intellectuals. Information technology explained why the American people and American authorities were so different from their European counterparts. It was popular among New Dealers—Franklin D. Roosevelt and his summit aides[25] idea in terms of finding new frontiers.[26] FDR, in jubilant the third anniversary of Social Security in 1938, advised, "There is nonetheless today a frontier that remains unconquered—an America unreclaimed. This is the not bad, the nation-wide frontier of insecurity, of homo want and fright. This is the frontier—the America—we have ready ourselves to repossess."[27] Historians adopted information technology, especially in studies of the w,[28] simply also in other areas, such equally the influential work of Alfred D. Chandler Jr. (1918–2007) in business history.[29]

Many believed that the terminate of the frontier represented the beginning of a new stage in American life and that the United States must expand overseas. Nevertheless, others viewed this interpretation every bit the impetus for a new moving ridge in the history of United States imperialism. William Appleman Williams led the "Wisconsin School" of diplomatic historians by arguing that the borderland thesis encouraged American overseas expansion, especially in Asia, during the 20th century. Williams viewed the frontier concept as a tool to promote democracy through both world wars, to endorse spending on foreign aid, and motivate action against totalitarianism.[xxx] Yet, Turner'south piece of work, in contrast to Roosevelt'due south work The Winning of the West, places greater emphasis on the evolution of American republicanism than on territorial conquest. Other historians, who wanted to focus scholarship on minorities, especially Native Americans and Hispanics, started in the 1970s to criticize the frontier thesis because it did not attempt to explain the development of those groups.[31] Indeed, their approach was to turn down the frontier as an of import process and to study the West as a region, ignoring the frontier experience east of the Mississippi River.[32]

Turner never published a major volume on the frontier for which he did 40 years of research.[33] Withal his ideas presented in his graduate seminars at Wisconsin and Harvard influenced many areas of historiography. In the history of religion, for example, Boles (1993) notes that William Warren Sweet at the University of Chicago Divinity Schoolhouse as well every bit Peter G. Fashion (in 1930), argued that churches adapted to the characteristics of the frontier, creating new denominations such as the Mormons, the Church of Christ, the Disciples of Christ, and the Cumberland Presbyterians. The borderland, they argued, shaped uniquely American institutions such as revivals, army camp meetings, and itinerant preaching. This view dominated religious historiography for decades.[34] Moos (2002) shows that the 1910s to 1940s black filmmaker and novelist Oscar Micheaux incorporated Turner's frontier thesis into his work. Micheaux promoted the West as a identify where blacks could feel less institutionalized forms of racism and earn economic success through hard work and perseverance.[35]

Slatta (2001) argues that the widespread popularization of Turner's frontier thesis influenced popular histories, motion pictures, and novels, which narrate the West in terms of individualism, frontier violence, and rough justice. Disneyland'southward Frontierland of the mid to late 20th century reflected the myth of rugged individualism that celebrated what was perceived to be the American heritage. The public has ignored academic historians' anti-Turnerian models, largely considering they conflict with and ofttimes destroy the icons of Western heritage. Yet, the work of historians during the 1980s–1990s, some of whom sought to bury Turner's formulation of the borderland, and others who sought to spare the concept but with dash, have done much to place Western myths in context.[36]

A 2020 written report in Econometrica found empirical support for the frontier thesis, showing that borderland experience had a causal impact on individualism.[37]

Early on anti-Turnerian thought [edit]

Though Turner's piece of work was massively popular in its time and for decades later, it received significant intellectual pushback in the midst of World State of war Two.[38] This quote from Turner's The Frontier in American History is arguably the most famous statement of his work and, to later historians, the most controversial:

American democracy was born of no theorist'south dream; it was non carried in the Susan Constant to Virginia, nor in the Mayflower to Plymouth. It came out of the American forest, and it gained new forcefulness each fourth dimension it touched a new frontier. Not the constitution but free land and an affluence of natural resources open up to a fit people, made the autonomous type of order in America for three centuries while it occupied its empire.[39]

This assertion's racial overtones concerned historians every bit Adolf Hitler and the Blood and soil ideology, stoking racial and subversive enthusiasm, rose to ability in Deutschland. An case of this concern is in George Wilson Pierson's influential essay on the frontier. He asked why the Turnerian American character was limited to the Thirteen Colonies that went on to form the United states, why the frontier did not produce that same character amid pre-Columbian Native Americans and Spaniards in the New World.[xl]

Despite Pierson and other scholars' work, Turner'south influence did not end during World State of war II or even later the war. Indeed, his influence was felt in American classrooms until the 1970s and 80s.[41]

New frontiers [edit]

President John F. Kennedy

Subsequent critics, historians, and politicians have suggested that other 'frontiers,' such equally scientific innovation, could serve similar functions in American development. Historians take noted that John F. Kennedy in the early 1960s explicitly called upon the ideas of the frontier.[42] At his acceptance speech upon securing the Autonomous Party nomination for U.Due south. president on July fifteen, 1960, Kennedy called out to the American people, "I am asking each of you to be new pioneers on that New Borderland. My call is to the young in heart, regardless of age—to the stout in spirit, regardless of party."[43] Mathiopoulos notes that he "cultivated this resurrection of frontier ideology as a motto of progress ('getting America moving') throughout his term of office."[44] He promoted his political platform every bit the "New Frontier," with a particular emphasis on space exploration and engineering. Limerick points out that Kennedy causeless that "the campaigns of the Sometime Borderland had been successful, and morally justified."[45] The "frontier" metaphor thus maintained its rhetorical ties to American social progress. The frontier thesis is one of the near influential documents on the American due west today.

Fermilab [edit]

Adrienne Kolb and Lillian Hoddeson argue that during the heyday of Kennedy's "New Frontier," the physicists who built Fermilab explicitly sought to recapture the excitement of the old frontier. They argue that, "Frontier imagery motivates Fermilab physicists, and a rhetoric remarkably similar to that of Turner helped them secure support for their research." Rejecting the Due east and West coast life styles that most scientists preferred, they selected a Chicago suburb on the prairie every bit the location of the lab. A minor herd of American bison was started at the lab's founding to symbolize Fermilab's presence on the frontier of physics and its connection to the American prairie. The bison herd still lives on the grounds of Fermilab.[46] Architecturally, The lab's designers rejected the militaristic design of Los Alamos and Brookhaven also as the academic architecture of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center. Instead Fermilab'due south planners sought to return to Turnerian themes. They emphasized the values of individualism, empiricism, simplicity, equality, courage, discovery, independence, and naturalism in the service of democratic access, human being rights, ecological remainder, and the resolution of social, economic, and political problems. Milton Stanley Livingston, the lab'southward associate director, said in 1968, "The frontier of high energy and the infinitesimally small is a claiming to the mind of human being. If nosotros tin can reach and cross this frontier, our generations will take furnished a significant milestone in human history."[47]

Electronic frontier [edit]

John Perry Barlow, along with Mitch Kapor, promoted the idea of internet (the realm of telecommunication) as an "electronic borderland" beyond the borders of whatsoever physically based regime, in which freedom and self-conclusion could be fully realized.[48] [49] Scholars analyzing the Internet have ofttimes cited Frederick Jackson Turner'southward borderland model.[fifty] [51] [52] Of special concern is the question whether the electronic frontier will broadly replicate the stages of development of the American state frontier.

People referenced by Turner [edit]

- Lyman Beecher

- Thomas Benton

- Edmund Burke

- John C. Calhoun

- Christopher Columbus

- Francis Grund

- Hermann von Holst

- Andrew Jackson

- James Madison

- James Monroe

- John Mason Peck

See also [edit]

- American frontier

- Discovery doctrine

- Borderland

- Rural history

- Frederick Jackson Turner

References [edit]

- ^ Saldaña-Portillo, María Josefina "Indian Given: Racial Geographies across Mexico and the United States," (2016) pp. 10

- ^ Turner, Frederick Jackson (1920). "The Significance of the Frontier in American History". The Frontier in American History. p. 293.

- ^ Turner, The Frontier in American History (1920) chapter 1

- ^ Allan 1000. Bogue, "Frederick Jackson Turner Reconsidered," The History Instructor, (1994) 27#2 pp. 195–221 at p 195 in JSTOR

- ^ Turner, Frederick Jackson (1920). "The Significance of the Borderland in American History". The Frontier in American History. p. 293.

- ^ Ostrander, Gilman (October 1958). "Turner and the Germ Theory". Agricultural History. 32 (iv): 258–261. JSTOR 3740063.

- ^ Ostrander, Gilman (October 1958). "Turner and the Germ Theory". Agricultural History. 32 (4): 259. JSTOR 3740063.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert (1890). Essays and Miscellany (First ed.). San Francisco: San Francisco, The History Company. p. 43.

- ^ Turner, Frederick. "The Frontier in American History". Project Gutenberg . Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ Stephenson, Carl (April 1946). "The Problem of the Mutual Human in Early on Medieval Europe". American Historical Review. 51 (iii): 419–438. doi:x.2307/1840107. JSTOR 1840107.

- ^ Slotkin, Richard (Winter 1981). "Nostalgia and Progress: Theodore Roosevelt'south Myth of the Frontier". American Quarterly. 33 (5): 608–637. doi:x.2307/2712805. JSTOR 2712805.

- ^ Slotkin, Richard (Winter 1981). "Nostalgia and Progress: Theodore Roosevelt'south Myth of the Frontier". American Quarterly. 33 (5): 608–637. doi:10.2307/2712805. JSTOR 2712805.

- ^ Slotkin, Richard (Winter 1981). "Nostalgia and Progress: Theodore Roosevelt'due south Myth of the Frontier". American Quarterly. 33 (5): 608–637. doi:ten.2307/2712805. JSTOR 2712805.

- ^ Sharon E. Kingsland, The Development of American Ecology, 1890–2000 (2005) p. 133

- ^ William Coleman, "Scientific discipline and Symbol in the Turner Frontier Hypothesis," American Historical Review (1966) 72#1 pp. 22–49 in JSTOR

- ^ Ray Allen Billington, America'due south frontier heritage (1974)

- ^ Porter, Robert; Gannett, Henry; Hunt, William (1895). "Progress of the Nation", in "Study on Population of the U.s. at the Eleventh Demography: 1890, Part 1". Agency of the Demography. pp. xviii–xxxiv.

- ^ Turner, Frederick Jackson (1920). "The Significance of the Frontier in American History". The Frontier in American History. p. 293.

- ^ Nash, Gerald D. (1980). "The Census of 1890 and the Closing of the Borderland". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 71 (three): 98–100. JSTOR 40490574.

- ^ Lang, Robert Eastward.; Popper, Deborah E.; Popper, Frank J. (1995). ""Progress of the Nation": The Settlement History of the Enduring American Frontier". Western Historical Quarterly. 26 (3): 289–307. doi:10.2307/970654. JSTOR 970654.

- ^ Turner, Frederick Jackson (1920). "The Significance of the Borderland in American History". The Frontier in American History. p. 1.

- ^ Walker D. Wyman and Clifton B. Kroeber, eds. Borderland in Perspective (1957)

- ^ Marvin G. Mikesell, "Comparative Studies in Frontier History," in Richard Hofstadter and Seymour Martin Lipset, eds., Turner and the Folklore of the Frontier (1968) pp. 152–72

- ^ Carroll, Dennis (1982). "Mateship and Individualism in Modern Australian Drama". Theatre Journal. 34 (4): 467–80. doi:x.2307/3206809. JSTOR 3206809.

- ^ Henry A. Wallace, New Frontiers (1934)

- ^ Gerald D. Nash, "The frontier thesis: A historical perspective," Journal of the West (Oct 1995) 34#4 pp. 7–xv

- ^ Franklin D. Roosevelt, Rendezvous with Destiny: Addresses and Opinions of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (2005) p. 130

- ^ Ann Fabian, "The ragged edge of history: Intellectuals and the American West," Reviews in American History (Sept 1998), 26#3 pp. 575–lxxx

- ^ Richard R. John, " Turner, Bristles, Chandler: Progressive Historians," Business History Review (Summertime 2008) 82#2 pp. 227–40

- ^ William Appleman Williams, "The Frontier Thesis and American Foreign Policy," Pacific Historical Review (1955) 24#four pp. 379–95. in JSTOR

- ^ Nichols (1986)

- ^ Milner (1991)

- ^ Ray Allen Billington, "Why Some Historians Rarely Write History: A Example Study of Frederick Jackson Turner," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. l, No. 1. (Jun., 1963), pp. 3–27. in JSTOR

- ^ John B. Boles, "Turner, the frontier, and the study of organized religion in America," Periodical of the Early Republic (1993) 13#2 pp. 205–xvi

- ^ Dan Moosd, "Reclaiming the Frontier: Oscar Micheaux equally Black Turnerian," African American Review (2002) 36#3 pp. 357–81

- ^ Richard W. Slatta, "Taking Our Myths Seriously." Journal of the West 2001 twoscore(3): 3–5.

- ^ Bazzi, Samuel; Fiszbein, Martin; Gebresilasse, Mesay (2020). "Frontier Culture: The Roots and Persistence of "Rugged Individualism" in the U.s.". Econometrica. 88 (6): 2329–2368. doi:10.3982/ECTA16484. ISSN 1468-0262.

- ^ Ostrander, Gilman (October 1958). "Turner and the Germ Theory". Agricultural History. 32 (4): 261. JSTOR 3740063.

- ^ Turner, Frederick. "The Frontier in American History". Project Gutenberg . Retrieved 20 Apr 2019.

- ^ Pierson, George (June 1942). "The Frontier and American Institutions: A Criticism of the Turner Theory". New England Quarterly. xv: 253. doi:10.2307/360525. JSTOR 360525.

- ^ Bogue, Alan (February 1994). "Frederick Jackson Turner Reconsidered". The History Instructor. 27 (2): 214. doi:ten.2307/494720. JSTOR 494720.

- ^ Max J. Skidmore, Presidential Performance: A Comprehensive Review (2004) p. 270

- ^ John Fitzgerald Kennedy and Theodore Sorensen, Let the Word Go Forth: The Speeches, Statements, and Writings of John F. Kennedy 1947 to 1963 (1991) p. 101

- ^ Margarita Mathiopoulos, History and Progress: In Search of the European and American mind (1989) pp. 311–12

- ^ Richard White, Patricia Nelson Limerick, and James R. Grossman, The Frontier in American Culture (1994) p. 81

- ^ Fermilab (30 December 2005). "Safety and the Surroundings at Fermilab". Retrieved 2006-01-06 .

- ^ Adrienne Kolb and Lillian Hoddeson, "A New Frontier in the Chicago Suburbs: Settling Fermilab, 1963–1972," Illinois Historical Periodical (1995) 88#1 pp. two–eighteen, quotes on p. 5 and 2

- ^ Barlow and Kapor (1990) "The Electronic Frontier"

- ^ Barlow (1996) "A Proclamation of the Independence of Cyberspace"

- ^ Rod Carveth, and J. Metz, "Frederick Jackson Turner and the democratization of the electronic frontier.," American Sociologist (1996) 27#i pp. 72–100. online

- ^ A.C. Yen, "Western Borderland or Feudal Society: Metaphors and Perceptions of Cyberspace," Berkeley Technology Police Journal (2002) 17#4 pp. 1207–64

- ^ East. Brent, "Electronic advice and folklore: Looking backward, thinking ahead, careening toward the next millennium," American Sociologist 1996, 27#1 pp. 4–10

Further reading [edit]

- The Frontier In American History the original 1893 essay by Turner

- Ray Allen Billington. The American Borderland (1958) 35 page essay on the historiography

- Billington, Ray Allen. Frederick Jackson Turner: historian, scholar, teacher. (1973), highly detailed scholarly biography.

- Billington, Ray Allen, ed,. The Frontier Thesis: Valid Interpretation of American History? (1966); the major attacks and defenses of Turner.

- Billington, Ray Allen. America's Frontier Heritage (1984), an analysis of Turner's theories in relation to social sciences and historiography

- Billington, Ray Allen. State of Savagery / Land of Promise: The European Image of the American Borderland in the Nineteenth Century (1981)

- Bogue, Allan 1000. . Frederick Jackson Turner: Strange Roads Going Downwardly. (1988), highly detailed scholarly biography.

- Brownish, David Southward. Beyond the Frontier: Midwestern Historians in the American Century. (2009).

- Coleman, William, "Science and Symbol in the Turner Frontier Hypothesis," American Historical Review (1966) 72#1 pp. 22–49 in JSTOR

- Etulain, Richard West. Does the Frontier Experience Make America Exceptional? (1999)

- Etulain, Richard W. Writing Western History: Essays on Major Western Historians (2002)

- Etulain, Richard W. and Gerald D. Nash, eds. Researching Western History: Topics in the Twentieth Century (1997) online

- Faragher, John Mack ed. Rereading Frederick Jackson Turner: "The Significance of the Frontier in American History". (1999)

- Hine, Robert V. and John Mack Faragher. The American West: A New Interpretive History (2000), deals with events, not historiography; concise edition is Frontiers: A Curt History of the American West (2008)

- Hofstadter, Richard. The Progressive Historians—Turner, Beard, Parrington. (1979). interpretation of the historiography

- Hofstadter, Richard, and Seymour Martin Lipset, eds. Turner and the Sociology of the Frontier (1968) 12 essays past scholars in different fields

- Jensen, Richard. "On Modernizing Frederick Jackson Turner," Western Historical Quarterly 11 (1980), 307-twenty. in JSTOR

- Lamar, Howard R. ed. The New Encyclopedia of the American West (1998), 1000+ pages of articles by scholars

- Milner, Clyde A., ed. Major Problems in the History of the American West 2nd ed (1997), primary sources and essays by scholars

- Milner, Clyde A. et al. Trails: Toward a New Western History (1991)

- Nichols, Roger L. ed. American Frontier and Western Issues: An Historiographical Review (1986) essays by xiv scholars

- Richard Slotkin, Regeneration through Violence: The Mythology of the American Borderland, 1600-1860 (1973), complex literary reinterpretation of the borderland myth from its origins in Europe to Daniel Boone

- Smith, Henry Nash. Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth (1950)

coppingerrunis1977.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frontier_thesis

ارسال یک نظر for "what argument did frederick jackson turner make to justify american imperialism?"